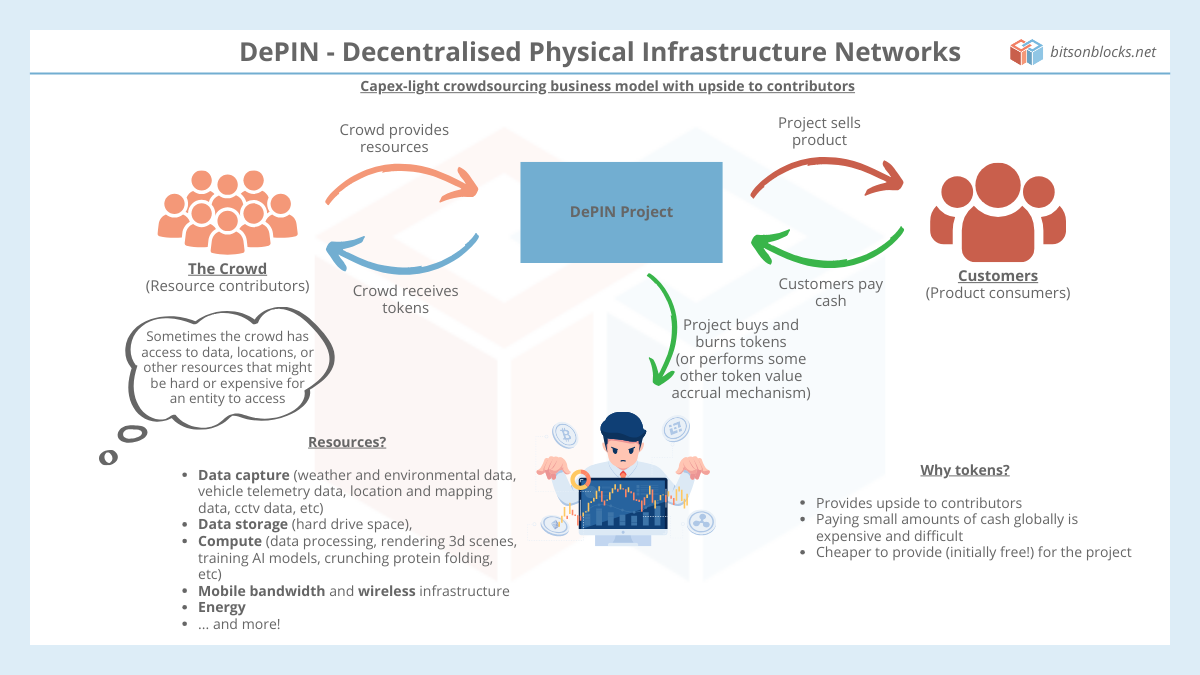

DePIN – “Decentralised Physical Infrastructure Networks” describes companies that are exploring a new capital-light crowdsourcing business model, where contributors participate in the success of the project.

DePIN companies crowdsource resources, sell a product to customers, and compensate the contributors with tokens, who share in the upside of the company’s success. This reduces the need for the company to have up-front capital to acquire the resources. Companies that need less capital can scale faster.

Examples of resources that can be crowdsourced include: all sorts of data capture (weather and environmental data, vehicle telemetry data, location and mapping data, cctv data, etc), data storage (hard drive space), compute (data processing, rendering 3d scenes, training AI models, crunching protein folding, etc), mobile bandwidth and wireless infrastructure, energy and more.

The intuition is that setting up and maintaining physical infrastructure is expensive and requires a lot of upfront capital; outsourcing some of that to the crowd in exchange for ongoing rewards is cheaper.

There are two important things going on here. First, this is a resurgence in crowdsourcing as a business concept, and second, tokens are being used to incentivise contributors, aligning them with the project’s success by giving them shared participation.

These concepts allow DePIN companies to scale quickly and cheaply. This is a new business model that can compete compellingly against capex-intensive, asset-heavy incumbents. It also opens up new business opportunities that would not be possible without incentivised crowdsourcing.

Existing business models

Crowdsourced resource business models already exist! I’m sure you’ve heard variants of the following:

“Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, owns no inventory. Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate.”

| Company | What resource is crowdsourced? | What do contributors get? |

| Uber | Cars & drivers | Cash |

| Content | A free social tool, dopamine | |

| Alibaba | Inventory | Cash |

| AirBnB | Accommodation | Cash |

These companies have become phenomenally successful by taking an asset-light crowdsourced resourcing approach.

Can we do better?

There are two arguments for how we can do better, one ideological, and one commercial.

Ideological: These companies have become too successful and powerful, and contributors feel like they haven’t participated in the success of the platforms that they have made successful. Where would Facebook be without user generated content? Why aren’t Facebook users paid? Is there room for a new, more equitable model where contributors share in the upside?

Commercial: How much more quickly could Airbnb grow, if home owners would receive shares of Airbnb as well as, or instead of, cash? (SEC security alert! Shares are securities! Fine… what if AirBnB financially rewarded contributors as a marketing/scaling tactic?) Would this attract more home owners to contribute? What if a new company came along which did this? Less margin, but potentially more scale.

So what’s new with DePIN? Where does crypto come in?

Instead of paying contributors in cash, resource coordinators (DePIN companies) pay contributors in tokens that they (or their Foundation) have created.

In some models, customers pay for the product in tokens too, but this is mostly unnecessary aside from the most permissionless / decentralised cases, and is annoying for the customer.

What are the pros and cons of paying contributors in tokens?

Pros and cons to the company: Tokens are free to create! So the company needs less cash to attract resource – at least initially. This allows for a company to start gathering resource without needing the initial capital to pay for it – it allows for a bootstrapping phase. However, contributors will want some value back, so the company will have to share future profit back to contributors.

Pros and cons to the contributor: Contributors accrue tokens whose value will be related to the company’s success. There is potential for the contributor to make much more back than accepting a flat cash payment, if the company is successful. However the exact mechanisms of how value is passed back to the token holder would weigh on whether regulators consider them as securities or not.

One model which seems to be popular now is “buy and burn“: projects use cash received from customers to buy tokens back from the open market, creating positive price pressure on the token, and destroy them. Another model is to figure out a way of distributing dividend-like payments to token holders, but this typically weighs the token more towards being regarded as a security, which has downsides. The industry keeps innovating around this value accrual topic.

At this stage few, if any, projects have spent more dollars buying and burning, than they have issued in new tokens.

Importantly for both the company and the contributor, DePIN projects incentivize creation of resource networks that a customer is willing to pay for, so there is a clear mechanic for value in and value out, unlike some other Ponzi-esque cryptoeconomic activities we have seen in the past.

Why not just pay contributors in cash?

It works in some cases – Uber pays the driver in cash. Yet there are benefits (and trade-offs) to token-based payments.

Tokens allow for upside to contributors, who may want to participate in the success of the project. If they don’t, they can simply sell the tokens immediately.

Paying small amounts of cash to people around the world via tradfi is expensive and complicated. Imagine trying to pay $3 to a million people. This is hard and expensive with bank accounts, but easy with stablecoins and tokens. So… use stablecoins?

The cash or stablecoins would need to come from somewhere. As discussed earlier, tokens can be created for free, so they are a great bootstrapping tool to get a company going, sharing some of the risk with contributors. Actually, this is also kind of the case with equity in the early stages of a company – shares are created for free, then given to early employees as incentives, instead of cash, and the early employees share in the risk and rewards of the company’s success.

How is sourcing from the crowd more efficient?

As a company, you price a product based on how much it costs to make, plus your profit margin. Your costs are an important factor here. How can a DePIN project source compute from the hodge-podge crowd more cheaply than Amazon can source it with its high negotiation power?

There are a couple of answers here.

Latent resource is cheaper to acquire than for-purpose resource. Some resources are latent, lying around. Think your laptop sitting idly with mostly empty hard drives, your gaming PC with the expensive GPU doing nothing while you’re at work, your spare bedroom gathering dust, or your phone that is gathering data as it accompanies you throughout the day. For these resources, you have already paid the capital costs, and any additional revenue would be extra pocket money. You didn’t buy them to make a profit, and unlike Amazon, you don’t need to recoup your capital costs within a timeline. You’re happy with anything you can get for it, so it can be acquired cheaply.

The crowd has access to physical geographical locations that might be expensive to acquire or impossible to access. For some types of DePIN, eg data gathering or network coverage, the crowd already has geographical rights (which it is happy to monetise) that a company would otherwise have to negotiate and pay for – if at all possible. The canonical example is cell towers for mobile data. It’s expensive and complicated to buy rights and build cell towers to cover a city. But it is much cheaper to incentivise households to put smaller devices up on their own roofs. As another example, if you wanted to gather sunlight brightness data from every bedroom and office building, this data would be very hard to get as a single company, but if you incentivised the crowd, it would be easy.

How can this scale for non-commodity resources?

Physical infrastructure is subject to wear and tear, and needs maintenance, sometimes extremely specialised. Who bears the cost of this maintenance? Laptops are one thing, but for more specialised hardware purchased by the crowd (crowdware?), the average household doesn’t have the expertise to maintain it.

Here we need to differentiate between latent resource and bought-for-purpose resource.

For latent resource (think laptops, gaming rigs, etc), the contributor has other reasons to own it, the revenue from contributing it is pocket money. The contributor is motivated to maintain uptime for non-financial reasons, so if it breaks, they will buy another one anyway.

For bought-for-purpose resource (think specific hardware sensors, or mobile communications devices), the contributor has clearly bought the device as an investment – to make profit – so they are financially motivated to maintain uptime. Typically, the contributor buys the hardware from the project, or a manufacturing partner of the project – the contributor bears the capital cost, and hopes to recoup it later with the token upside. In this case the maintenance should be done by the the project, or a third party specialist under some sort of contract or guarantee. It is typically in the interest of both the project and the contributor to keep the thing running.

Who should watch out?

If your incumbent business is quite capital intensive, could a crowd-funded competitor emerge? If your business requires geographical dispersion, could households or other parties participate by effectively renting out their real estate? Is there latent supply of the raw materials for your product or service that could be gathered, if contributors were financially incentivised? This DePIN model can be applied quite widely.

Do contributors have to pay tax on their revenue?

Of course you do.

Are DePIN tokens securities?

It depends ?

Thanks to my colleague Tanay Nandgaonkar for edits and comments to the post.